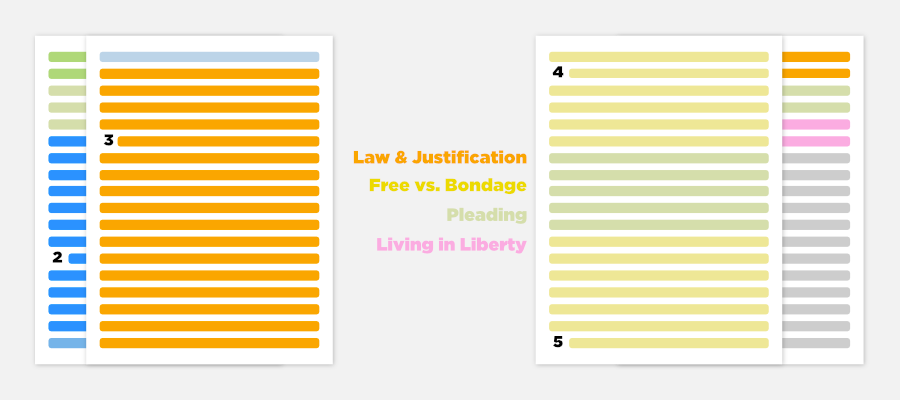

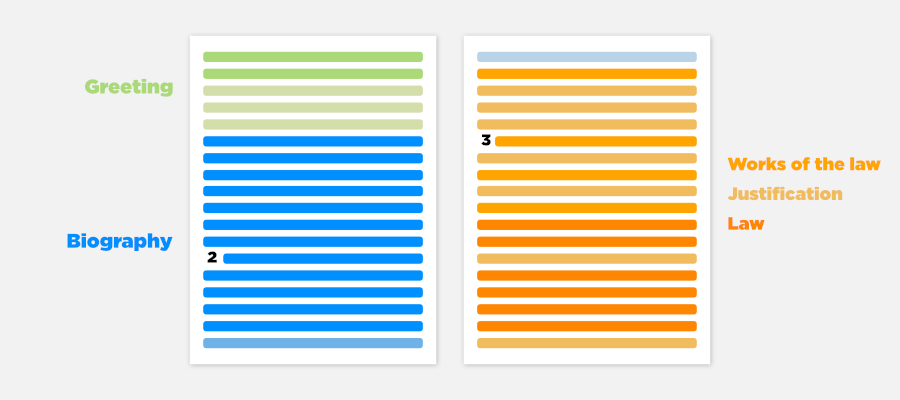

We've left off (after what I hope was a sufficiently meticulous breakdown) with Paul presenting the problem at hand: Christian Jews have been (falsely) teaching the newer Christian Gentiles in Galatia that their new faith requires obedience to the Mosaic law. Both in the "completion" or proof of their initial salvation, as well as the nomistic sense of how they are meant to live their Christian life. Chapter 3, verse 3 in particular lays that out, which as a commentary elaborates (emphasis mine):

The main point of Paul's rhetorical question here, however, has to do with the incongruity of beginning one's Christian life on one basis ("with the Spirit") and then shifting somewhere in progress to another basis ("by human effort"). What Paul wants his converts to see is that the Christian life is one that starts, is maintained, and comes to culmination only through dependence on the activity of God's Spirit (cf. 5:25; also see Phil 1:6, where the same verbs ἐκάνπμιαζ and ἐπζηεθές appear and where the point is made that completion of the Christian life comes about on the same basis as its inception, viz. by God's working).

Word Biblical Commentary, Richard Longenecker, pp. 103- 104

It's not too hard to imagine why the Galatians succumbed to such teachings. As a new father, it would certainly be beneficial, perhaps even relieving, to have a simple rulebook with a list that I could check off to fulfill my fatherhood correctly. Sure it might be a little tedious, but as long as I have this "official" compilation of dad rules, I can't go wrong. Having a brand new life enter your own with the sole task of "loving him" can almost seem daunting and overly vague, yet we'd all be in agreement that it would be foolish to assume a rulebook and checklist would be the "correct" choice, or even realistic option, in this case. Similarly, the Galatians may have latched on to the Judaizers' teachings and tried to integrate the Torah into their own life as the easy, God-approved checklist, as to avoid sinning in their new walk. However living in this manner was never the intention in the first place, especially in the case of the Gentiles.

Paul begins to elaborate how the believers' faith (both initially and continually) is not connected to obeying (doing works of) the Law, but to Christ and Christ only. Paul explains the purpose and towards the end of chapter 3 compares it to a tutor we are no longer under. Starting with 3:26, we are going to start a transition into another analogy (in the form of an allegory). The transition will connect back to the tutor concept, as well as connect the allegory with another concept that Paul has been slowly building throughout the chapter.

Believers are sons (and daughters) of God. As such, all their other earthly distinctions such as ethnicity, social status, and even gender mean nothing when compared to the "child of God" status. As believers, and therefore God's children, Paul then connects us to Abraham's seed (this time in the plural, children sense), which as we can see with the "neither Jew nor Greek" from earlier, should be taken in the spiritual sense as opposed to the Jewish thinking that it was only through their bloodline. Since Abraham was given a promise, we as his seed then get to inherit (are heirs) to this promise. The imagery continues:

"A child is basically a servant" is sort of the idea presented here. Despite his inheritance, he does not wield any power until a certain time. He learns from others (tutors and governors) on how to use his inheritance perhaps, but until then he effectively has the same "power" as a mere servant.

Focusing on the true spiritual implications of this analogy, we can see that now with Christ (his coming being equated to the "fullness of time") we have received adoption. In this initial portion (v5) Paul is addressing Jews specifically as noted by the "redeem those who were under the law" as well as Paul's inclusion of himself into the group, "that we might." Gentiles were never under the law, so logically we're talking about the Jewish subset of believers at the moment.

Also worth noting, Christ came to redeem those who were under the Law, not those who are. I think this actually an important distinction to make as Paul could have easily used the latter to clarify whether or not those believers would continue in it. Instead, he references the submission to the Law in a past tense. The pattern should be clear:

- 3:13-14, from curse to blessing

- 3:23, from imprisonment to freedom

- 3:24-25, from tutor to no tutor

- 4:2, under tutors and governors to (functionally) lord of all

- 4:5, under the law to no longer under the law

Paul then flips to address the Gentiles, who were in a slightly different scenario, but parallel the pattern through the letter so far.

- 4:8-9, did not know God to know God

After at least 6 comparisons of where the believers have been to where they are now, Paul finally comes to the error. That is, the action that reverses the correct pattern that has been established. After knowing God they desire to return to bondage, in other words, they desire to live under the (Mosaic) law. They have already started in fact, hence this whole letter! We even see that in verse 10 Paul alludes to their observation of days, months, seasons, and years, which through all the previously established context, would refer to the Sabbath and feasts.

It is worth pointing out how the mention of these traditional Jewish customs by the Galatians are surrounded by a "desire again to be in bondage" and "I am afraid for you," a clear negative view by Paul in the Galatians' actions. Paul fears that after having taught the Galatians about the freedom they have in their faith in Christ, they are "returning to the basics" as it were. Taking a step back from their rightful position as heirs, to that of a child who requires a tutor.

Here Paul gives a glimpse into the start of his ministry with the Galatians. It appears that he had never originally intended to actually preach the gospel here (at least, in that moment in time), but due to circumstances of health, was basically stuck there a while. Through his (apparently trialsome) recovery, he went ahead and taught the gospel to his gracious Gentile helpers. Paul offers warm words of praise to their hospitality.

That praise to their hospitality is then contrasted to their apparent rejection of Paul and his message after the Judaizers' teachings. We see here that part of the Judaizers' efforts involves isolating the Galatians to only hear/consult from the Judaizers, and perhaps to begin separating themselves from Paul, despite all the labor he poured into them through the start of their walks. Paul is clearly upset and shares these feelings with his Galatian brothers and sisters.

Paul now transitions to a very strong allegory, which seems targeted at the Judaizers specifically (or at the very least, the Jews within the Galatian churches and perhaps the Gentiles already digging into Torah), as it requires knowledge of the Torah to fully appreciate.

These things are an allegory, for these are the two covenants. The one is from Mount Sinai, which gives birth to bondage; she is Hagar. Now this Hagar is Mount Sinai in Arabia, and represents the present Jerusalem, and is in bondage with her children. But the Jerusalem which is above is free, which is our mother.

The classic story of Abraham is brought up (in an almost sarcastic "law keepers, have you even read the law?" sort of way) and then immediately explained as to leave no room for doubt:

There are two covenants. One is from Mount Sinai, which can only refer to the Mosaic covenant, as that is where God gave Moses the law. This covenant, the one from Mount Sinai, gives birth to bondage. Note that this is the exact verbiage Paul has been using in the letter so far (imprisonment/bondage), and it is being directly tied to the Sinai covenant (and by proxy, the law). This is worth highlighting as even today, modern day law-keepers tend to dismiss the notion that the Law is tied to any sort of "bondage," but rather deflect that attribute to the oral law or anything else. Paul is crystal clear on what this covenant is, to who it applies ("present Jerusalem"), and repeats again the connection to bondage. "But...", Paul continues, the other covenant, the Jerusalem which is above (spiritual) is not in bondage, but free. That Jerusalem, is "our mother." The Jews and any listener with a hint of Jewish history would know who this refers to.

“Rejoice, barren woman

who does not bear;

break forth and shout,

you who have no labor pains!

For the desolate has many more children

than she who has a husband.”

Now we, brothers, like Isaac, are the children of promise. But as it was then, he who was born after the flesh persecuted him who was born after the Spirit, so it is now also. Nevertheless what does the Scripture say? “Cast out the slave woman and her son, for the son of the slave woman shall not be heir with the son of the free woman.” So then, brothers, we are not children of the slave woman, but of the free woman.

For freedom Christ freed us. Stand fast therefore and do not be entangled again with the yoke of bondage.

Paul introduces the other mother by quoting Isaiah 54. Here it is revealed that Sarah (the barren woman), the mother of Isaac, is the mother of the child of promise. The one that represents the freedom in Christ.

The allegory does not end there though! Paul is making it clear that "...as it was then...", those born of the flesh (Ishmael in the original story, or those tied to the old Mosaic covenant per the allegory) persecute those born after the Spirit (Isaac/those living in the new covenant under Christ's freedom). I'm not particularly sure what the extent of Ishmael's original persecution was. There is mention of some mocking in Genesis 21:9, and we do see some verses later that he married an Egyptian woman (so perhaps, through descendants, the persecution continued), but despite the lack of details there the imagery is still clear.

Paul ties it all up with the starting verse in Chapter 5: he does not want believers "entangled again with the yoke of bondage," that is, the Mosaic law. All believers are now free in Christ, that freedom He had promised so long ago with which we now, as heirs of His kingdom and promises, live under instead of the former tutor.

Paul rewinds all the way to the start of the issue, referencing again the Judaizers and their teaching (which we can see as well in Acts 15 is that 'You must be circumcised and keep the law') which has now plagued the new Galatian believers.

Circumcision, under the context of what's happening and the heart behind it, does not profit the Gentiles (or Jews for that matter) in any way concerning their salvation (or their Christian walk). In fact, by doing so and placing themselves under the law, they are now obligated to keep all of it, and as such, must be justified by it rather than Christ. Again, it is not that circumcision itself is an evil deed, or a random tradition that God implemented for no particular reason in a former covenant. Rather, for the gentile Galatians, this imposed requirement or the submission to such will not bring about any extra merit before God and shows a lack of faith in the power of the Spirit. Paul warns those who have that they have fallen from grace, a brutal accusation, but one that he has to say in love to his Galatian brothers. Faith is what matters, not works.

You, brothers, have been called to liberty. Only do not use liberty to give an opportunity to the flesh, but by love serve one another. For the entire law is fulfilled in one word, even in this: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” But if you bite and devour one another, take heed that you are not consumed by one another.

You can really feel Paul's emotion as he pleads with the Galatians. They were doing so well but were then persuaded to lies. Paul still appears to have hope for them though. As for the teachers of this "yeast," we see what Paul wishes of them.

Paul clarifies, however, a very important point. Here, liberty (or being "without a law") does not mean any sort of permission to live immorally. The freedom of Christ entails serving one another in love. So important is this single point, that Paul even says the whole law is fulfilled in doing just that. That's quite the lifted burden, when rather than living through the bondage of following 613 rules we can obey a single command: love your neighbor as yourself.

Paul will continue to elaborate on some details of living in this freedom, and what comes out of it, as he closes his letter to the Galatians. We will take a look at this in the final post for this series.