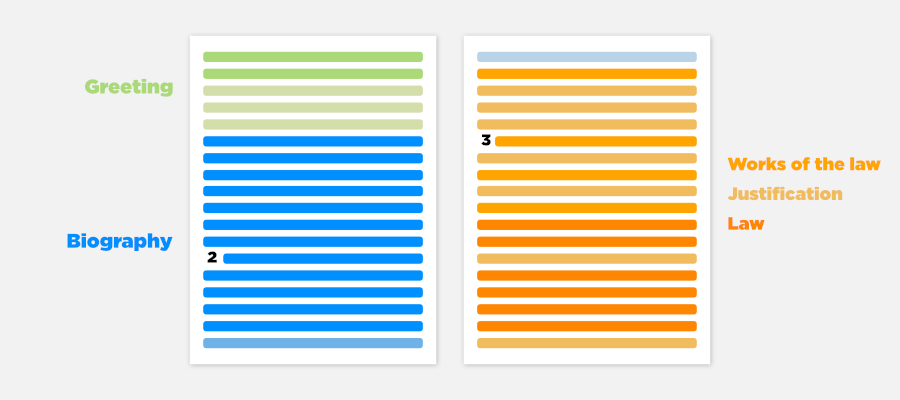

We left off with Paul's mini-biography in the first half of Chapter 2, with some mention of Titus and circumcision pressure from "false brothers". We are now transitioning into the heart of Galatians, and the issue at hand. This will cover a lot of material, so be warned of the lengthy read!

But when I saw that they were not straightforward about the truth of the gospel, I said to Peter before them all, “If you, being a Jew, live like a Gentile and not like a Jew, why do you compel the Gentiles to live like Jews?”

Here, another (tangential) issue emerges. That is, the hypocrisy of Peter while eating with Gentiles. It would appear that initially, and fearfully, Peter would separate himself from the Gentile believers because of the judgment of other Jews. Paul confronted him publicly about the issue (knowing that there were many others following in his footsteps) as this gave an incoherent and distorted image to those around him. In the original Greek, the usage and contrast of the "being a Jew/the Gentiles" words (Ioudaios and ta ethnē respectively) implies a context that should be read more accurately as "if you, a Jewish believer, can live like a Gentile and not like a Jew, how can you compel Gentile believers to become Jews?" On top of that, the usage of the second instances ("live like a X") use the words that more directly relate to the customs of each ethnicity (Ioudaïkōs and ethnikōs respectively).

In other words, considering the context of the situation here, Paul is implying that Peter (a Jewish believer) is behaving with the customs of a Gentile during his table fellowship rather than his own customs as a Jew, i.e. not following the dietary laws of Torah. There would only be a handful of other customs a Christian Gentile would differentiate from in comparison to a Christian Jew (the portions of the law that are generally labeled as the "ceremonial" laws) but seeing as how the scene involves eating, it is probably that custom Peter is being hypocritical about upon the presence of the incoming men of James.

This would be opposed to those who teach that what Peter was actually doing was just "breaking oral law" which looked down upon fellowship with the Gentiles at all. Although it is true that was a thing some Jews had at the time, it is not part of the context that Paul has established here. We'll expand on that in a moment, for now we can observe a fairly summarized version of the issue at hand: compelling Gentiles to live like Jews.

If, while we seek to be justified by Christ, we ourselves also are found to be sinners, is Christ therefore the minister of sin? God forbid! For if I build again the things which I destroyed, I make myself a transgressor.

For through the law I am dead to the law, that I might live for God. I have been crucified with Christ. It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh, I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave Himself for me. I do not nullify the grace of God. For if righteousness comes by the law, then Christ died in vain.

Dr. Constable's commentary on Galatians makes an interesting note with verse 15:

Unsaved Jews regarded Gentiles as “sinners.” Paul ironically referred to them as that since Peter was discriminating against them by behaving as he had.

“This characterization at once focuses attention on the sharp distinction between Jew and Gentile, for what made the Gentiles sinners in the estimation of the Jews was not only that they did not observe the law but also that they did not even possess it and consequently lacked the possibility of obtaining righteousness through it.”

That being said, Peter knows better than that (especially considering his own experience with Cornelius!) in that Christ came for everyone, as we are all sinners who need justification through Him. Justification does not come by works of the law. This issue was important to Paul, because by Peter's actions he not only caused other Jewish believers to stumble along with him, but he also set a scenario that basically diminished his Gentile brethren to some lower, "incomplete" class of Christian, that wasn't worth or welcome to partake in fellowship with the Jewish believers unless they (the Gentiles) became more like the Jews.

Once again, with both groups already under the understanding of Christ and his saving grace, the things the Gentiles would have to do to be "accepted" as "true" brethren would have to be the extra "ceremonial" customs found in Torah. This obligation to the Gentiles is not part of the true gospel, and hence we can better understand Paul's harsh rebuke to observing Peter and company's behavior.

Paul's dead to the law imagery is better elaborated in Romans 7 so I won't go into the details for this post, but what Paul is doing is setting up a contrast and how now his life for God is one lived through faith in Christ.

works of the law

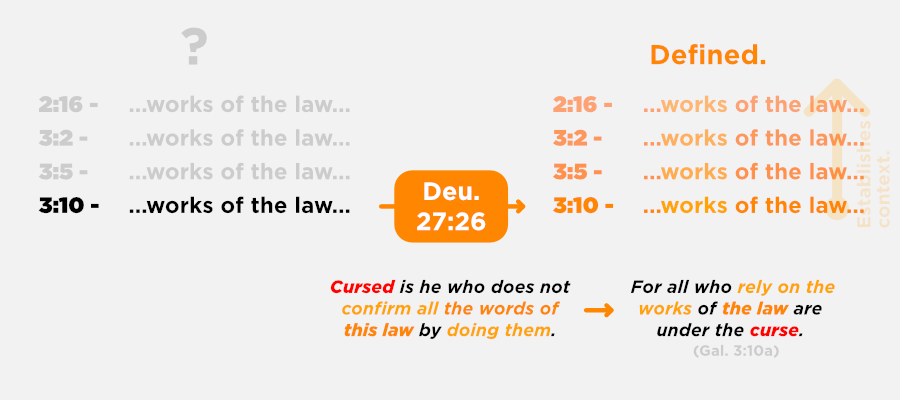

It is also worth clarifying and elaborating on this phrase: the works of the law here are exactly what they sound like. In other words, it is not works (actions/effort of your own part) of the (Mosaic) law through which we receive justification. Verse 15 makes a clear distinction between the Jew and Gentile, and as Constable states that difference is primarily the Mosaic law. I point this out as there are other doctrines that would like to change the context (and therefore meaning) of what's being said here, despite the lack of any other contextual evidence indicating anything of the sort.

This will, inevitably, alter everything you understand in Galatians, so let's focus on this to make sure we have a solid foundation for the rest of this book. Again, your whole understanding of Galatians is basically hinged on the definition of this phrase, so I urge for a fair assessment of what the evidence best supports.

As far as I've been able to gather, the primary, alternative doctrine seems to teach that the works of the law here is in reference to the oral law (i.e. the Talmud, a superset of man-made laws added onto the Mosaic law with apparent equal, or even greater, authority) and not the Mosaic law. The only "evidence" I have come across for redefining it this way apparently relies on 2 reasons: the first because of the allusion in 1:14 where Paul mentions how he was "...more exceedingly zealous for the traditions of my fathers." and the second is a manuscript from the Dead Sea Scrolls (4QMMT). I'm going to focus on what Galatians has to say first, and address the document toward the end, hopefully demonstrating how weak of a support piece both end up being when we simply allow scripture to interpret scripture.

Contextual definition

It is interesting to note that this is actually the first instance of the exact phrase works of the law, if we think of the NT books chronologically (most sources state Galatians was written before Romans, which is the only other book that uses the phrase like this). Not only that, but Galatians is actually the book that contains 4 of the 5 instances of it! In other words, if for some reason the meaning of works of the law is unclear or questioned (which I personally think is impossible without, unfortunately, some form of eisegesis in play), Galatians should definitely be the primary book to define it for us, if at all possible, before having to resort to any other documents.

Using this approach, let's first look at verse 14 in context, that being that the verse is in the middle of a clear biographical portion of the letter. What is the purpose of this portion? To claim the single verse is meant to set the context of the rest of the book is an enormous jump in logic and is ripping the verse out of its context for another purpose. It is a single verse in a large set of verses, with no clear emphasis to indicate any importance regarding the specific claim that works of the law is works of the oral law. What is emphasized in this portion should be easily recognized:

- v16b-17 I did not immediately confer with flesh and blood, nor did I go up to Jerusalem to those who were apostles before me

- v19-20 I saw none of the other apostles except James, the Lord’s brother. In what I am writing to you, before God, I do not lie!

- v22 and was unknown by face to the churches of Judea which were in Christ.

- 2:6 But of these who seemed to be something—whatever they were, it makes no difference to me; God shows no partiality to anyone—for those who seemed to be something added nothing to me.

- 2:10 Only they requested that we should remember the poor, which I also was eager to do.

In the first 3 items we see the emphasis that Paul's message was not altered by anyone, as he was initially very secluded and at most met with 2-3 disciples. The latter 2 items conclude the biography by emphasizing that after meeting with the 2-3 (and eventually some more), his message was still not altered, but rather he was accepted as-is (minus the reminder about the poor, which wasn't in regards to his actual message). The only reason Paul even bothers mentioning his zeal in verse 14, as far as we can tell by the text, is to apparently create the sharp contrast of how this "super Jewish" life he had before (where he persecuted Christians) has now been replaced with his new Christian life, where he is now preaching to make more Christians across the world. Quite the transformation!

I find this to be a much more harmonious reading between the 2 chapters, as do numerous commentaries. If the emphasis was on setting the context for the rest of the letter, and to redefine the works of the law phrase, then why are there no other supporting verses in the context? We have to jump from v14 in chapter 1 all the way to v16 in chapter 2 with no repetition, confirmation, or reminder (which we just demonstrated with his "nothing added to me" point) that these works are of the traditions spoken of previously.

On that note, why does Paul even bother referring to it as law when he had already established them as traditions of my fathers beforehand? He could of easily repeated this phrase to avoid any confusion for someone to "mistake" it with the Mosaic Law (which I think is indisputably the first thing that comes to mind when reading, and probably what came to mind to those who heard the letter at the time too). In fact, is there even any verse in the NT that clearly equates the law (nomos in the Greek) to the oral law? As far as my searches have indicated, every instance of the oral law is referenced as "(your) tradition(s) (of men/elders/fathers)" by Paul or Christ, and never simply as nomos. If nomos is ever used for anything other than Mosaic Law (and I'm aware it is, at times), there is always some context or indicator to denote it in the very same verse.

Hopefully, that provides a sufficient case as to why v14 does not alter the context of the phrase works of the law since the portions are completely separate to begin with. We can continue to analyze the proper context, and the other 3 instances of the phrase, in chapter 3 of Galatians:

Paul is fired up again in his disappointment. He asks the Galatians who has fooled them and whether their salvation (which is symbolized by receiving the Spirit), or miracles they apparently are witness to, came from their keeping of Torah or whether it was through the faith they had upon hearing the true gospel message. Paul continues with the questioning, and has begun the comparison that you will see throughout the rest of the book: faith versus works.

Some doctrines may want to point out how they are in agreement that justification starts with faith, and that following Torah is not what gets you saved, however I find this to be a bait and switch tactic since it is still then disputed afterward that to truly prove or show that you have received justification/salvation, then you still have to follow it.

Imagine you're thirsty and have been wandering for hours in a desert when you come across an oasis. You approach it to have a man interrupt you for a moment to explain how he is the keeper of the oasis, and to drink from here all you need to do is wear a bracelet which you graciously accept. Being told after you've begun drinking the water that there are now some expectations in place should you wish to continue to drink would be very deceptive! Honestly, I think it's worse than just being told at the start that you'd need to meet these expectations to have or maintain the bracelet, since at least that way you are aware of the deal.

I believe the issue at hand in Galatians encompasses both the "start" of the Christian life, as well as the Christian life itself. This idea is well elaborated by the scholar Richard Longenecker who states in his Galatians commentary (emphasis mine):

On a practical basis, the opponents at Galatia must also have included in their message an emphasis on the Jewish law as the divinely appointed way to check libertinism within the church. Paul's emphases on (1) the pedagogical function of the law coming to an end with Christ, in 3:19–4:7, and (2) living by the direction of the Spirit (as opposed to life directed by law) as the antidote to libertinism, in 5:13–26, suggest that not only did the opponents argue circumcision as a prerequisite for being fully accepted by God but also that they asserted that life lived under the Torah — which meant for them a Jewish lifestyle — was the only way to bring the excesses of the flesh into line.

The repeated mention of "the flesh" (ζάνλ, or "the sinful nature") in 5:13–21 implies quite clearly that the Galatian churches were having ethical problems or at least were acutely conscious of ethical failures. For such problems the Judaizers offered a rather straightforward and seemingly God-honoring solution: accept a Jewish nomistic lifestyle and you will have clear guidance as to what is right and wrong, and so be able to live a life that pleases God. Just as Paul's message, they probably added, being only elemental in nature, was not able to relate you properly to Abraham and the Abrahamic covenant for full salvation, so it failed to relate you to the divine Torah and a Jewish lifestyle for proper Christian living.

Thus you need to accept circumcision to be fully accepted by God into the Abrahamic covenant, and you need to take on a Jewish lifestyle in order to live in a manner that checks the excesses of your sinful, Gentile natures and enables you to please God in your lives. Their message was, therefore, in effect, one of both legalism for full salvation and nomism for Christian living (cf. my Paul, Apostle of Liberty, 78–83, on the use of "legalism" and "nomism").

Word Biblical Commentary: Galatians, pg 44

To clarify, when Longenecker speaks of libertinism and the way to keep it in "check" or the "antidote" to it, it is in reference to how the Galatians should "live their life" in a way that isn't free (liberty, hence libertinism) of all moral obligations. The seemingly obvious and logical suggestion a Jew could make would be to follow/live by Torah (nomism, or religious conduct based on law), as they had done for so long. Surely it would be of benefit to the lawless Gentiles, who now with the freedom of Christ, may take their freedom as some license to continue in sin.

It's not that the idea is void of logic, or that it couldn't have been made with good intentions, but it is clear that, in Galatia, the Judaizer's pressure and obligation to do so has gone beyond this and into the realm of a false gospel. Let us also not forget that Paul introduces the whole issue starting with Peter and his disagreement with the notion to "compel the Gentiles to live like Jews".

For all who rely on the works of the law are under the curse. For it is written, “Cursed is everyone who does not continue in all things which are written in the Book of the Law, to do them.” Now it is evident that no man is justified by the law in the sight of God, for “The just shall live by faith.” But the law is not of faith, for “The man who does them shall live by them.” Christ has redeemed us from the curse of the law by being made a curse for us—as it is written, “Cursed is everyone who hangs on a tree” — so that the blessing of Abraham might come on the Gentiles through Jesus Christ, that we might receive the promise of the Spirit through faith.

Knowing then that there is no room to read the "oral law" into the context of Galatians, and understanding therefore that the Judaizers aren't simply focusing on Torah at the start, but also as the way to continue living, let's recap the instances here:

- 2:16 - yet we know that a man is not justified by the works of the law, but through faith in Jesus Christ. Even we have believed in Christ Jesus, so that we might be justified by faith in Christ, rather than by the works of the law. For by the works of the law no flesh shall be justified.

- 3:2 - I want to learn only this from you: Did you receive the Spirit through the works of the law, or by hearing with faith?

- 3:5 - Does God give you the Spirit and work miracles among you by the works of the law, or by hearing with faith?

- 3:10 - For all who rely on the works of the law are under the curse. For it is written, “Cursed is everyone who does not continue in all things which are written in the Book of the Law, to do them.”

These are the 4 places Galatians uses works of the law. Moving forward, Galatians will transition to just explaining the history and purpose of the law, and considering the smoothness of the texts we've had since the end of chapter 2, it would make sense that whatever the law is in these 4 verses is the same law expressed in the rest of the letter (as well as across all 4 verses, of course). Otherwise, we would be claiming that Galatians is alternating between definitions of a single word (with no clear contextual indications) in a very incoherent manner.

With that in mind, 2:16 gives us our first instance of the phrase. It serves as an introduction to the concept, primarily by presenting it as antithetical to "faith in Christ". I believe there are some extra parallels to be drawn from this, but I will mention those in a separate section and only point out the initial contrast for now.

Verses 3:2 and 3:5 simply continue the contrasts, this time to "receiving the Spirit/work miracles among you" by hearing with faith versus works of the law. Neither of these verses specifically (nor 2:16 if we ignore the future parallels) add any direct indication to what law is being referenced, which implies to me that it should be obvious upon reading. I believe that "obviously implication" is really the first hint to all of this, and initial impressions for anyone who has read or is simply aware of the Bible's history will probably justly synonymize "the law" as being "the Torah".

That being said, 3:10 should be the one to secure that notion. Importantly, it indicates an important consequence: those relying on works of the law are under a curse. So there is an effect (curse) in place for the people who depend on this law. Where does this curse come from? Paul is quoting Deuteronomy 27:26 which specifically states:

In other words, this law (as stated in Deuteronomy) has a curse for those who can't confirm all the words it contains. What is "this law"? The Torah, which Deuteronomy is a part of, of course! Therefore, "those who rely on works (can't confirm all the words of) the law (this law, Torah)" would be the way to define what Paul is trying to say. Paul is literally ("for it is written") defining it for us through his reference to Deuteronomy!

Paul reaffirms then (in v11) that it is evident no man is justified by the Law (Torah, which should be clear by the context now since we're still talking about the justification through it) but rather by faith. This creates a specific contrast between law and faith. Note in particular that the contrast is "live by faith", which I believe implies a contrast against (living) by the Law. This supports the "legalistic and nomistic" context that we elaborated on above.

Paul confirms this again in v12 by quoting a part of Leviticus 18:5, "The man who does them shall live by them." In other words, the man who does (works) them (the law) shall live by them (and not by faith). The issue at hand is not simply a prerequisite the Judaizers are imposing on Gentiles, it is a lifestyle. Christ has fortunately taken this whole situation into his own hands, when He died for us. By doing this, He has enabled the blessings of Abraham (promise of salvation) to be received by the Gentiles (who did not have or live by the Law, and therefore not know of God and their sinful state) through (living by) faith in Jesus Christ.

I want to requote this portion in the NET, as I think it gives an easier read of what is being said here:

The point is two-fold: first is that covenants are solid when they are by humans, and so especially when they involved God. Second is that the path of the promises leads to Christ. In other words, Paul is clarifying how the promise of inheritance (which we can also understand spiritually as salvation and justification) were ultimately done and given to Abraham through Christ, and not by "the law that came 430 years later" which, if that isn't about as clear as it gets, was the Torah given to Moses. Once again Paul adds another key point in the thread of this law he speaks of. The inheritance therefore has no basis (i.e. they are totally unrelated in this area) whatsoever on Torah, if it did, it would be making void the promise to Abraham, and you can't void one of God's promises!

A logical follow-up question arises then, and Paul answers it immediately knowing it would be made by his critics (which we will mention towards the end too). What's the point of the law then, if it has nothing to do with our salvation or justification? If following that wasn't what was saving Jews to begin with (or proving they were), why even have it? What's its purpose? Although not quite clarified here, transgressions (sin) seems to be the primary reason for its creation. Whether that is to show people their sin, stop them from sinning, something else, or all of it together, is not clear yet but we can probably assume something along those lines.

It certainly created a standard for Israel compared to the rest of the world, and if followed properly, should have kept them more morally pure than if they did not have it. Regardless, if sin was its reason for being, then it should come to no surprise that it was added "until the Seed should come", that being Christ, the one who has conquered sin once and for all. In other words, Christ's coming and promise supersedes (or in Christ's own words, fulfills, and therefore completes and finishes) whatever the Law's purpose was.

Again before the criticism can be made, Paul clarifies another concern: is the Law contrary to the promises of God? The word contrary here is also translated as opposed, against, or contradict in other versions. The answer is no, it is not. With all of Paul's apparent negativity toward the Law (considering all the contrasting he's done against it and the Spirit/faith which he links to the true gospel), it almost becomes necessary to clarify that the Law isn't some random anomaly that God created for no reason, nor is it an evil thing that contradicts God in any way. If the Law was enough to do the whole job, then Paul says it would have been so, however this is not the case.

Here we get more elaboration for the questions we had in vv19-20. Paul compares the law to a tutor, one that would point to and bring us to Christ. Now that Christ has come, we don't need the tutor anymore. We know who He is, how to identify Him, and can follow Him directly without need of the tutor's instructions. We also see a repeat of some imagery Paul is using, and will continue to use later on: "confined all things under sin" and "imprisoned under the law". This vocabulary is worth remembering when we go into the next part of Galatians. To conclude this post's direct commentary on Galatians, I am firmly convinced that the law (and any works of) mentioned throughout the letter are in reference to a single, coherent instance: that being the Mosaic Law and its purpose within the life of a Christian (in this case, emphasis on the Gentile believers).

Biblical Support

I want to provide some extra supporting portions in other biblical manuscripts, specifically in demonstrating that it is Mosaic law being referenced in Galatians. There is actually a lot of support if you look across all the epistles, but I will leave that for another day and focus here by looking at the parallels that tie directly to the final verse of chapter 2: "For if righteousness comes by the law, then Christ died in vain." This comparison is found in other books too, which should put to rest any fear that accepting the "works of Mosaic law" definition in Galatians is somehow incoherent with the rest of scripture.

Paul, later on in Romans, parallels the previous concept. God sent his own Son because the law wasn't enough. I see no way to twist this mention of law as "oral law", especially since verse 4 speaks of the "righteous requirement" that was fulfilled by Christ. Christ clearly has not died to fulfill the "righteous requirements" of the oral law. Therefore, we can logically conclude that "Christ died so we may obtain righteousness that we couldn't achieve through the Law", i.e. the same thing Galatians 2:21 says. Similarly:

In Hebrews 7 we see the same thing, a "weak law" that required a better hope (Christ) to finalize things. If you read this chapter in context, it should undoubtedly demonstrate that this law, again, is not the oral law but the law of Moses (given to Levitical priesthood, as mentioned in v11). I think these pair of verses show a clear coherency with what Paul is saying in Galatians 2, and added with all the context of chapters 1 and 2, along with the mountain of support from everything else mentioned, should suffice as evidence to, at the very least, be the stronger interpretation of what works of the law actually means.

Non-biblical Support

Finally, we can come back to address the second piece of support the works of the oral law using group maintains. Right off the bat I find it very concerning that we are going to (re)define a phrase in the Bible based off non-biblical sources. This goes against one of the best rules for proper exegesis where we let scripture define scripture, as we have done previously now using Galatians first, and then other NT examples.

I am well aware that historical documents of the time can provide extra insight, cultural context, or unique guidance into the writings of the Bible but when you are risking the core doctrine of a whole letter, which in turn can alter the doctrine of the NT and Christianity as a whole, wouldn't it be prudent to use the letter itself as the primary source of definition and then, if needed, provide multiple external resources as support?

The Qumran document apparently "lists the works of the law", which of course is really a list of things that man has added onto God's law. The interesting thing about the document is that it appears to be the only other document (outside of Galatians/Romans) from that time to use that exact works of the law phrase. So the logic of the Torah observers would then be that this list of works is more accurate to what Paul meant in Galatians, since that is "how it was used" according to this one document. This is somehow supposed to be of heavier weight than the fact that Paul himself, in Galatians 3:10, directly quotes Deuteronomy 27:26 which is actually wrapping up its own list in context. More importantly, it also references "this law" (the same one with the curse as those who rely on the works of it) which would have to refer to Torah. Of course, we are also putting aside all the other contextual support we have already gone through as well. My question would be why are we even looking for an external definition at this point? It honestly seems to me a simple case of trying to support the presumption rather than showing evidence that supports the scripture itself.

I have looked for additional support to this understanding, but the only thing I can find to support the "Talmudic definition" of works of the law from extra-biblical sources, is this single manuscript from, what appears to be, a Sadduccean sect known as the Qumran. This theory seems to have been started by, or at least popularized around 1994 after Martin Abegg made the "discovery" of the same term Paul used, in the manuscripts.

Interestingly enough, what I did find were not one, or two, but three unique documents that indicate what an actual Jewish perspective of what Paul's message sounded like.

They then claim that he was Greek, and the son of a Greek mother and Greek father, but that he had gone up to Jerusalem, stayed there for a while, desired to marry a daughter of the high priest, and had therefore became a proselyte and been circumcised. But since he still could not marry that sort of girl he became angry and wrote against circumcision, and against the Sabbath, and the legislation.

The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis: Book I (sects 1-46), pg 144

Here we see what appear to be a bunch of lies that some Jews had conjured up against Paul and his message. Note, however how they twist his message! Paul has never been against any of the things they stated (even in Galatians), however Paul was against the obligation of these things as relating to the Christian walk, and this is what the accusing Jews (and probably the Judaizers in Galatians) latched on. This is very similar to the way the accusations against the martyr Stephen twisted his words in Acts 6:14. It would be fair, of course, to make the counter argument that with everything else being a "complete" lie, the latter accusations are as well. However, this becomes unlikely considering our other 2 references.

An even clearer indication of this debate is found in the material pertaining to the Kerygmata Petrou, a major source of the Pseudo-Clementine literature. ... The book of Peter's preachings, the actual Kerygmata Petrou, is no longer extant; all or parts of it have been absorbed into different sections of the Pseudo-Clementine Recognitions and Homilies. In his epistle Peter asks James not to pass on the contents of his preaching to any Gentiles or any Jews who have not completed the proper probation (1:2). Rather, these teachings are to be given to the seventy brethren so that they can prepare those who are to be teachers (2:1). This procedure is necessary to combat the Gentiles who have rejected his lawful preaching in preference to the lawless doctrine of his enemy (2:3).

The Gospel of Matthew and Christian Judaism, pg 185

The enemy here, is Paul, who preaches against the "lawful preaching" of Peter. This, of course, was not actually written by the true Peter.

It is argued that Paul cannot have been given the teaching of Jesus in a vision because he does not agree with the teaching of Peter and James. Nor can Paul be an apostle, because he is not one of the twelve (Recognitions 4.35). His lawless gospel is a false doctrine which cannot be approved by James (Homilies 11.35.4-6; Ep. P. 2.3f.). Here the motif of the primacy of James has an anti-Pauline intent. It is Peter who takes the true law-based gospel to the Gentiles.

The Brother of Jesus: James the Just and His Mission, pp 38-39

So we have the Panarion of Eiphanius, along with the Recognitions and Homilies (which in turn quote from the Kerygmata Petrou) all pointing to this idea that Paul's gospel was "lawless", which again is a twisting of the true message Paul was actually giving. Nonetheless, this is how believing Jews perceived his writings in the first through third centuries. It doesn't take much to see that this seems to be the exact line of thinking the Judaizers had during the time of Galatians (or at the very least, this would be the result of Paul's rebuttal). So how do these 3 documents weigh compare to the single Qumran document (which doesn't even talk about Paul, it relies solely on the coincidental usage of the same phrase from Galatians)? I think the fairest result would be to tip the scales to the idea that whatever Paul was saying was not perceived by his readers as against the oral law, but rather the Torah (even if, some took that to the incorrect extreme).

This whole situation has disturbing parallels to another case of incorrect interpretation of scripture: the Jehovah Witness's handling of John 1:1. Basically every other scholar or teacher has understood and taught that John knowingly wrote the "Word was God" (just like how works of the law is almost unanimously understood as "works of Torah"), but JW's always argued that the Greek is missing the "a" article but that it should be there and that it is the correct interpretation (a conclusion they must reach for their presumption that Christ isn't God to be true, just how works of the law must mean something else to someone who believes in modern-day Torah observance). Then around comes the discovery of some Coptic texts (or this Qumran document) that suddenly gives a historical piece of evidence that somewhat (the links in both cases are fair to make, but to claim it as irrefutable evidence or as anything worth building a foundation on is exceedingly dangerous) supports their modern theory. They only have the one piece, but clearly it works as sufficient proof to alter the whole foundation of their belief of the Bible and one of its core doctrines.

Although I am not remotely an expert on the ways to analyze historical documents and what ultimately is chosen as the more accurate translation of works, nor will I ever claim to, I do not see that as a requirement to be capable of recognizing just how poor and careless of a method the JW's are using for their biblical understanding, and I find the handling of 4QMMT to be the exact same mistake.

As such, and believing scripture to continue being a whole, coherent piece (and Galatians to likewise follow this pattern) I cannot accept this alternative definition and hope I have presented a well sustained case as to what I find to be the correct interpretation of Galatians. Moving forward, we will continue under the basis that Paul is coherently referring to the Mosaic law throughout the letter, as he transitions topics a bit.